You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

[*KPC WOT*] Who are the Fake Meat Investors ?

- Thread starter kaypohchee

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?kaypohchee

Arch-Supremacy Member

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2005

- Messages

- 15,493

- Reaction score

- 600

https://twitter.com/TristanHaggard/status/1173643147202703362

Tristan Haggard@TristanHaggard

Important thread on the real reason behind the anti meat propaganda

and plant based diet for "sustainability" narrative push. Share/ retweet

Quote Tweet

Tristan Haggard@TristanHaggard

Sep 16

This Carbon Markets refauxlution has been planned for years by the

World Bank, IMF, NGO's and global corporate interests.

Get ready for more shilling and praising the global wartime-style

economic plunder and global taxing of all life.

Big $ eugenics lurks under the green mask

https://twitter.com/GHGGuru/status/1173389146179555328

Show this thread

1:01 AM · Sep 17, 2019·Twitter for Android

Dokken Tow@DokkenTow

In Alaska some stores make it expensive to buy meat that isn't a

processed frozen something. They also charge more for steaks that

are horribly cut and are brown not from using pineapple or something

else to cook it.

They really don't want people to eat anything good for us.

https://twitter.com/TristanHaggard/status/1173598685546143744

https://twitter.com/GHGGuru/status/1173389146179555328

Frank Mitloehner@GHGGuru

Sep 16

@DerSPIEGEL reported about a change in German climate policy.

They state that the former focus on personal action involving reduced

flying, move to vegetarianism/veganism and less driving will not make a major dent. Germany will put a price on carbon to affect systemic change.

Frank Mitloehner@GHGGuru

In short: I see signs of major players abandoning the “change what

you eat to safe the climate” narrative, toward one that makes carbon emissions expensive making alternatives work. Source:

Streit um Gesetz: Warum die Klimawende gelingen kann - SPIEGEL ONLINE - Wirtschaft

Die deutsche Energiewende? Ein Desaster. Nun aber soll es einen Neustart in der Klimapolitik geben. Die Voraussetzungen dafür sind günstig wie nie - nicht wegen, sondern trotz der Politik.

spiegel.de

Frank Mitloehner@GHGGuru

I also observed this change in narrative during the recent democratic presidential debates.

Things are moving in the right direction - a true chance for our climate.

I will discuss this issue with members of the CA legislature later this

coming week. Stay tuned.

8:12 AM · Sep 16, 2019 from Davis, CA·Twitter for iPhone

Frédéric Leroy@fleroy1974

Good. But what's the chance that this will also translate into a systemic

"meat tax"? Either because of ignorance or as a symbolic move?

Frank Mitloehner@GHGGuru

Currently, meat in Germany is taxed at 7% and most other food at 19%.

The discussion is not to tax meat at a higher rate than the rest but to bring

it up to the same rate. I don’t think even that will happen but we shall see.

Evidence Driven Carnivore@MikeEnRegalia

Actually all food (produce) is taxed at 7%. This change would single out

meat as a non-food, which would be a horrible move.

Frank Mitloehner@GHGGuru

I don’t think there is a chance for that to happen. A few German politicians

did bring up raising meat VAT to 19% but (to my knowledge), it went nowhere. However, these rumors were broadcasted throughout the world’s media as a serious major policy move in a major G20 country.

Demare@DemareGerry

It’s always been about the money. The early work was just to precondition

the populace into paying the taxes.

Joe Cloud@joeblueskies

To quote my dad -“Praise The Lord.” He was a formerly brilliant but

severely brain-injured PhD engineer. Wasn’t much for talking, but used

to say that when he saw something necessary was happening.

(Also used when he had to take a piss and we found a men’s room for him).

Tristan Haggard@TristanHaggard

Important thread on the real reason behind the anti meat propaganda

and plant based diet for "sustainability" narrative push. Share/ retweet

Quote Tweet

Tristan Haggard@TristanHaggard

Sep 16

This Carbon Markets refauxlution has been planned for years by the

World Bank, IMF, NGO's and global corporate interests.

Get ready for more shilling and praising the global wartime-style

economic plunder and global taxing of all life.

Big $ eugenics lurks under the green mask

https://twitter.com/GHGGuru/status/1173389146179555328

Show this thread

1:01 AM · Sep 17, 2019·Twitter for Android

Dokken Tow@DokkenTow

In Alaska some stores make it expensive to buy meat that isn't a

processed frozen something. They also charge more for steaks that

are horribly cut and are brown not from using pineapple or something

else to cook it.

They really don't want people to eat anything good for us.

https://twitter.com/TristanHaggard/status/1173598685546143744

https://twitter.com/GHGGuru/status/1173389146179555328

Frank Mitloehner@GHGGuru

Sep 16

@DerSPIEGEL reported about a change in German climate policy.

They state that the former focus on personal action involving reduced

flying, move to vegetarianism/veganism and less driving will not make a major dent. Germany will put a price on carbon to affect systemic change.

Frank Mitloehner@GHGGuru

In short: I see signs of major players abandoning the “change what

you eat to safe the climate” narrative, toward one that makes carbon emissions expensive making alternatives work. Source:

Streit um Gesetz: Warum die Klimawende gelingen kann - SPIEGEL ONLINE - Wirtschaft

Die deutsche Energiewende? Ein Desaster. Nun aber soll es einen Neustart in der Klimapolitik geben. Die Voraussetzungen dafür sind günstig wie nie - nicht wegen, sondern trotz der Politik.

spiegel.de

Frank Mitloehner@GHGGuru

I also observed this change in narrative during the recent democratic presidential debates.

Things are moving in the right direction - a true chance for our climate.

I will discuss this issue with members of the CA legislature later this

coming week. Stay tuned.

8:12 AM · Sep 16, 2019 from Davis, CA·Twitter for iPhone

Frédéric Leroy@fleroy1974

Good. But what's the chance that this will also translate into a systemic

"meat tax"? Either because of ignorance or as a symbolic move?

Frank Mitloehner@GHGGuru

Currently, meat in Germany is taxed at 7% and most other food at 19%.

The discussion is not to tax meat at a higher rate than the rest but to bring

it up to the same rate. I don’t think even that will happen but we shall see.

Evidence Driven Carnivore@MikeEnRegalia

Actually all food (produce) is taxed at 7%. This change would single out

meat as a non-food, which would be a horrible move.

Frank Mitloehner@GHGGuru

I don’t think there is a chance for that to happen. A few German politicians

did bring up raising meat VAT to 19% but (to my knowledge), it went nowhere. However, these rumors were broadcasted throughout the world’s media as a serious major policy move in a major G20 country.

Demare@DemareGerry

It’s always been about the money. The early work was just to precondition

the populace into paying the taxes.

Joe Cloud@joeblueskies

To quote my dad -“Praise The Lord.” He was a formerly brilliant but

severely brain-injured PhD engineer. Wasn’t much for talking, but used

to say that when he saw something necessary was happening.

(Also used when he had to take a piss and we found a men’s room for him).

kaypohchee

Arch-Supremacy Member

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2005

- Messages

- 15,493

- Reaction score

- 600

Continuation

https://twitter.com/TristanHaggard/status/1173598685546143744

Tristan Haggard@TristanHaggard

This Carbon Markets refauxlution has been planned for years by the

World Bank, IMF, NGO's and global corporate interests. Get ready for more shilling and praising the global wartime-style economic plunder and global taxing of all life. Big $ eugenics lurks under the green mask

Tristan Haggard@TristanHaggard

The "4th industrial Revolution" will be sold as the solution

- financialization of all resources and "carbon" in a global market where all resources (including us, who are considered human cattle), movement, and action are tracked by global big tech/date for the World Bank/IMF.

This is the reason behind the #climate crisis war propaganda that's been blasted into our skulls for decades - the "threat" must be met in a

global war effort, the consolidation of all economies into Carbon Markets. Guess who stands to benefit from this massive theft[/COLOR]

Merck Family Fund, Rockefeller Foundation, Packard Foundation, Michelin Corporate Foundation, Ford Foundation, Boeing Company, Bloomberg Philanthropies, David Rockefeller Fund, Rockefeller Brothers Fund,

Rockefeller Family Fund, Wells Fargo | all on board

Climate Change - Funders — Inside Philanthropy

https://www.insidephilanthropy.com/fundraising-for-climate-change

And of course, the World Bank is licking it's chops as the big banks,

NGO's, massive corporations, and big $ fauxlanthropy unveil

CARBON PRICING in the 4th Industrial Revolution global economic prison.

Big tech/data and social credits will be crucial.

Pricing Carbon

Carbon Pricing initiative

https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/pricing-carbon#CarbonPricing

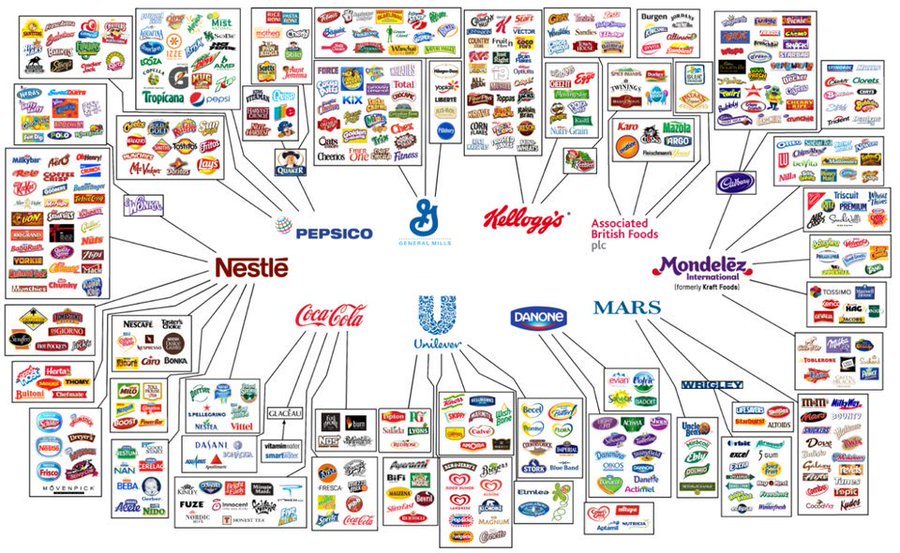

Cargill is also at the forefront of "sustainable development" and

"Carbon Pricing" rhetoric, along with Unilever, Marck, Bayer-Monsanto, Google, Wal-Mart and others who stand to benefit from

this massive global economic fraud behind the green mask.

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development, of which EAT, of the Eat-Lancet report, is a partner is

a major driving force behind the push towards this new 4th Industrial Revolution technocratic control grid climate cult taxation scheme.

the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, @wbcsd markets this global fraud as "progress" and "environmental stewardship", "equality" and "justice" for people and nature.

Take a look the companies are behind WBSCD...this is who stands to benefit:

These member companies want to save the planet and bring "equality"

and "justice" to the poor and the environment?

TBC - Part 2

https://twitter.com/TristanHaggard/status/1173598685546143744

Tristan Haggard@TristanHaggard

This Carbon Markets refauxlution has been planned for years by the

World Bank, IMF, NGO's and global corporate interests. Get ready for more shilling and praising the global wartime-style economic plunder and global taxing of all life. Big $ eugenics lurks under the green mask

Tristan Haggard@TristanHaggard

The "4th industrial Revolution" will be sold as the solution

- financialization of all resources and "carbon" in a global market where all resources (including us, who are considered human cattle), movement, and action are tracked by global big tech/date for the World Bank/IMF.

This is the reason behind the #climate crisis war propaganda that's been blasted into our skulls for decades - the "threat" must be met in a

global war effort, the consolidation of all economies into Carbon Markets. Guess who stands to benefit from this massive theft[/COLOR]

Merck Family Fund, Rockefeller Foundation, Packard Foundation, Michelin Corporate Foundation, Ford Foundation, Boeing Company, Bloomberg Philanthropies, David Rockefeller Fund, Rockefeller Brothers Fund,

Rockefeller Family Fund, Wells Fargo | all on board

Climate Change - Funders — Inside Philanthropy

https://www.insidephilanthropy.com/fundraising-for-climate-change

And of course, the World Bank is licking it's chops as the big banks,

NGO's, massive corporations, and big $ fauxlanthropy unveil

CARBON PRICING in the 4th Industrial Revolution global economic prison.

Big tech/data and social credits will be crucial.

Pricing Carbon

Carbon Pricing initiative

https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/pricing-carbon#CarbonPricing

Cargill is also at the forefront of "sustainable development" and

"Carbon Pricing" rhetoric, along with Unilever, Marck, Bayer-Monsanto, Google, Wal-Mart and others who stand to benefit from

this massive global economic fraud behind the green mask.

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development, of which EAT, of the Eat-Lancet report, is a partner is

a major driving force behind the push towards this new 4th Industrial Revolution technocratic control grid climate cult taxation scheme.

the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, @wbcsd markets this global fraud as "progress" and "environmental stewardship", "equality" and "justice" for people and nature.

Take a look the companies are behind WBSCD...this is who stands to benefit:

These member companies want to save the planet and bring "equality"

and "justice" to the poor and the environment?

TBC - Part 2

kaypohchee

Arch-Supremacy Member

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2005

- Messages

- 15,493

- Reaction score

- 600

Cont'd Part 2

Tristan Haggard@TristanHaggard

"Carbon Pricing" is global financialization of all life, control of all resources

by global corporate technocratic council to save us from the #ClimateCrisis

- THIS is the narrative that the mouthpieces will be soon praising, the

@WBCSD members couldn't be more pleased.

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development: these champions

of the greenwash are pushing global dietary guidelines (#plantbaseddiet)

as well as a #NewDealforNature, the solution to the problems which the

#ClimateCrisis war propaganda presents

@wbcsd promotes the #NewDealForNature - this fuzzy propaganda term

will soon get more PR. It will entail global megamarkets based on

"Natural Capital" and "Payments for Ecosystem Services", trojan horse

terms for ways global megacorporations can greenwash and fund further scaling

"Ecosystem System Services" - will we pay carbon offsets to the

World Bank so @LeoDiCaprio can profit on the 1,000's hectares he owns

in Ecuador through his fauxlanthropy NGO?

@wbcsd @UN @WWF @RockefellerFdn have a very interesting way of

saving the planet from the #ClimateCrisis

And of course, this all boils down to control of resources...including "human resources".

Julian Huxley, internationalist eugenicist and first Director of @UNESCO

founded The World Wildlife Fund @WWF

@WWF is also pushing the #plantbaseddiet as a response to the

#ClimateCrisis war propaganda rhetoric. Julian Huxley's

eugenics family's influence continues to push for technocratic elite control

of all resources, people, and land.

and the soon to be mainstream idea of "Natural Capital" and

"Ecosystem Payment Services" are solutions that @WWF The World

Wildlife Fund says will save the planet...

turning the whole world into a digitized carbon trading scheme.

Marco Lambertini, Director General, @WWF International and contributor

to @EATforum Eat-Lancet Commission. #plantbaseddiet and global dietary guidelines

(aka processed cheap crap) funded and subsidized by a massive global financial fraud

shell system of "Carbon Pricing"

Continuation Part 3

Tristan Haggard@TristanHaggard

"Carbon Pricing" is global financialization of all life, control of all resources

by global corporate technocratic council to save us from the #ClimateCrisis

- THIS is the narrative that the mouthpieces will be soon praising, the

@WBCSD members couldn't be more pleased.

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development: these champions

of the greenwash are pushing global dietary guidelines (#plantbaseddiet)

as well as a #NewDealforNature, the solution to the problems which the

#ClimateCrisis war propaganda presents

@wbcsd promotes the #NewDealForNature - this fuzzy propaganda term

will soon get more PR. It will entail global megamarkets based on

"Natural Capital" and "Payments for Ecosystem Services", trojan horse

terms for ways global megacorporations can greenwash and fund further scaling

"Ecosystem System Services" - will we pay carbon offsets to the

World Bank so @LeoDiCaprio can profit on the 1,000's hectares he owns

in Ecuador through his fauxlanthropy NGO?

@wbcsd @UN @WWF @RockefellerFdn have a very interesting way of

saving the planet from the #ClimateCrisis

And of course, this all boils down to control of resources...including "human resources".

Julian Huxley, internationalist eugenicist and first Director of @UNESCO

founded The World Wildlife Fund @WWF

@WWF is also pushing the #plantbaseddiet as a response to the

#ClimateCrisis war propaganda rhetoric. Julian Huxley's

eugenics family's influence continues to push for technocratic elite control

of all resources, people, and land.

and the soon to be mainstream idea of "Natural Capital" and

"Ecosystem Payment Services" are solutions that @WWF The World

Wildlife Fund says will save the planet...

turning the whole world into a digitized carbon trading scheme.

Marco Lambertini, Director General, @WWF International and contributor

to @EATforum Eat-Lancet Commission. #plantbaseddiet and global dietary guidelines

(aka processed cheap crap) funded and subsidized by a massive global financial fraud

shell system of "Carbon Pricing"

Continuation Part 3

kaypohchee

Arch-Supremacy Member

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2005

- Messages

- 15,493

- Reaction score

- 600

Cont'd Part 3

Tristan Haggard@TristanHaggard

Social Credit system beta tested by Google in China right now will allow

total technocratic control of payments and production.

The "4th Industrial Revolution" 5g IoT along with social media will be the backbone interface of the new Carbon Payments global financial system.

"Carbon Pricing" IS the Social Credit system being tested in China,

simply rebranded and marketed to us as a solution to the #ClimateCrisis

war propaganda. Meat tax is just the beginning.

@nytimes, member of @wbcsd pushing for new globally regulated

"Carbon Pricing" and "Payments for Ecosystem Services" markets with

the World Bank, IMF, big foundations, and global megacorporations,

running ads for the mass astroturfing of another #ClimateCrisis war rally

Tristan Haggard@TristanHaggard

Social Credit system beta tested by Google in China right now will allow

total technocratic control of payments and production.

The "4th Industrial Revolution" 5g IoT along with social media will be the backbone interface of the new Carbon Payments global financial system.

"Carbon Pricing" IS the Social Credit system being tested in China,

simply rebranded and marketed to us as a solution to the #ClimateCrisis

war propaganda. Meat tax is just the beginning.

@nytimes, member of @wbcsd pushing for new globally regulated

"Carbon Pricing" and "Payments for Ecosystem Services" markets with

the World Bank, IMF, big foundations, and global megacorporations,

running ads for the mass astroturfing of another #ClimateCrisis war rally

kaypohchee

Arch-Supremacy Member

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2005

- Messages

- 15,493

- Reaction score

- 600

https://twitter.com/KetoCarnivore/status/1174591973312929793

Ken D Berry MD@KenDBerryMD

Is @timhortons sending the right message to Canadians by yanking

plant-based meat-like products?

Tim Hortons to stop selling Beyond Meat products at most

locations in Canada | CBC News

Tim Hortons is pulling Beyond Meat products from Canadian locations

outside Ontario and B.C., but the parent company of the fast-food chain

says it may bring the plant-based protein foods back later...

https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/tim-hortons-beyond-meat-plant-diet-vegan-vegetarian-1.5288349

I am n=1@iamnequals1

This is encouraging. I was concerned that they were trying to socially

engineer us towards the other direction, by slowly providing ONLY

plant-based options. I regained my health and took control of my life by

COMPLETELY eliminating processed garbage, such as these fake meats.

L. Amber O'Hearn@KetoCarnivore

My understanding was that Beyond subsidised trials with many retailers.

Tim's apparently didn't see it as viable after the trial.

3:52 PM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPad

juice the journalist@juice_journo

Tim Hortons are still selling Beyond fake meat in two regions, though.

L. Amber O'Hearn@KetoCarnivore

Presumably the two regions where they predict profit.

juice the journalist@juice_journo

Yeah, you'd think so. Presumably they're the most "woke" parts of Canadia.

An Aging Scientist@ddhewitt68

Interesting. Any idea how significant the subsidies were?

Extracts from https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/tim-hortons-beyond-meat-plant-diet-vegan-vegetarian-1.5288349

"Both the Beyond Burger and Beyond Meat breakfast sandwiches were introduced as a limited time offer. We have particularly seen positive reaction to our Beyond Meat offering in Ontario and B.C., especially in breakfast, and are proud to offer both alternatives in those regions."

Plant-based eating trend

But plant-based proteins — or even proteins in general — aren't part of the core business of Tim Hortons, said Sylvain Charlebois, director of the Agri-food Analytics Lab, and professor in food distribution and policy at Dalhousie University in Halifax.

"Timmies is all about coffee, doughnuts and muffins. They just rode on this Beyond Meat bandwagon, and that's dangerous because they tried to capitalize on a brand and not necessarily a product," he said.

"It's like the pizza at McDonald's. It was a disaster back in the '80s because nobody goes to McDonald's to eat pizza."

Charlebois said his data shows B.C. has the highest rate of veganism in the country and Ontario has the highest rate of vegetarianism, which may explain the decision to continue offering Beyond Meat breakfast sandwiches in those provinces.

"I was a bit surprised by Quebec because in Quebec, the Beyond Meat product is selling very well in retail stores, but I guess Quebecers just didn't want to buy it in a restaurant," said Charlebois.

He said the decision is a blow for Beyond Meat.

"Beyond Meat's strategy is all about developing channels to connect with the public. They don't spend a dime on publicity or marketing. Zero. They just capitalize in their relationships with franchises in order to sell their products.

"It's a bit dangerous to do that because if someone pulls [the product], like a major restaurant chain like Tim Hortons, that's going to send the wrong signal to Canadians or to the public."

Ken D Berry MD@KenDBerryMD

Is @timhortons sending the right message to Canadians by yanking

plant-based meat-like products?

Tim Hortons to stop selling Beyond Meat products at most

locations in Canada | CBC News

Tim Hortons is pulling Beyond Meat products from Canadian locations

outside Ontario and B.C., but the parent company of the fast-food chain

says it may bring the plant-based protein foods back later...

https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/tim-hortons-beyond-meat-plant-diet-vegan-vegetarian-1.5288349

I am n=1@iamnequals1

This is encouraging. I was concerned that they were trying to socially

engineer us towards the other direction, by slowly providing ONLY

plant-based options. I regained my health and took control of my life by

COMPLETELY eliminating processed garbage, such as these fake meats.

L. Amber O'Hearn@KetoCarnivore

My understanding was that Beyond subsidised trials with many retailers.

Tim's apparently didn't see it as viable after the trial.

3:52 PM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPad

juice the journalist@juice_journo

Tim Hortons are still selling Beyond fake meat in two regions, though.

L. Amber O'Hearn@KetoCarnivore

Presumably the two regions where they predict profit.

juice the journalist@juice_journo

Yeah, you'd think so. Presumably they're the most "woke" parts of Canadia.

An Aging Scientist@ddhewitt68

Interesting. Any idea how significant the subsidies were?

Extracts from https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/tim-hortons-beyond-meat-plant-diet-vegan-vegetarian-1.5288349

"Both the Beyond Burger and Beyond Meat breakfast sandwiches were introduced as a limited time offer. We have particularly seen positive reaction to our Beyond Meat offering in Ontario and B.C., especially in breakfast, and are proud to offer both alternatives in those regions."

Plant-based eating trend

But plant-based proteins — or even proteins in general — aren't part of the core business of Tim Hortons, said Sylvain Charlebois, director of the Agri-food Analytics Lab, and professor in food distribution and policy at Dalhousie University in Halifax.

"Timmies is all about coffee, doughnuts and muffins. They just rode on this Beyond Meat bandwagon, and that's dangerous because they tried to capitalize on a brand and not necessarily a product," he said.

"It's like the pizza at McDonald's. It was a disaster back in the '80s because nobody goes to McDonald's to eat pizza."

Charlebois said his data shows B.C. has the highest rate of veganism in the country and Ontario has the highest rate of vegetarianism, which may explain the decision to continue offering Beyond Meat breakfast sandwiches in those provinces.

"I was a bit surprised by Quebec because in Quebec, the Beyond Meat product is selling very well in retail stores, but I guess Quebecers just didn't want to buy it in a restaurant," said Charlebois.

He said the decision is a blow for Beyond Meat.

"Beyond Meat's strategy is all about developing channels to connect with the public. They don't spend a dime on publicity or marketing. Zero. They just capitalize in their relationships with franchises in order to sell their products.

"It's a bit dangerous to do that because if someone pulls [the product], like a major restaurant chain like Tim Hortons, that's going to send the wrong signal to Canadians or to the public."

Last edited:

kaypohchee

Arch-Supremacy Member

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2005

- Messages

- 15,493

- Reaction score

- 600

https://twitter.com/8WeekBloodSugar/status/1174440875654615041

Mark Hancock@8WeekBloodSugar

Will it only change when there’s no more money to be made?

Quote Tweet

Mark Gregory ن

←Gammon@thebiggrog

←Gammon@thebiggrog

No surprises here.

5:51 AM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPhone

Graham Phillips@grahamsphillips

This is the cause

Graham Phillips@grahamsphillips

We're up against two huge sets of vested interests

Prof. Steve Cox@gpdiarist

Sugar is the most commonly abused addictive drug in the Uk and western world @lowcarbGPm @DocRunner1 . Until we remove it from daily snacking and eating opportunities diabetes will continue to rise.

Sugar food industry and Pharma partnership opposing this????

Dave@Dave06031956

Hmmmmm

Mark Hancock@8WeekBloodSugar

Will it only change when there’s no more money to be made?

Quote Tweet

Mark Gregory ن

No surprises here.

5:51 AM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPhone

Graham Phillips@grahamsphillips

This is the cause

Graham Phillips@grahamsphillips

We're up against two huge sets of vested interests

Prof. Steve Cox@gpdiarist

Sugar is the most commonly abused addictive drug in the Uk and western world @lowcarbGPm @DocRunner1 . Until we remove it from daily snacking and eating opportunities diabetes will continue to rise.

Sugar food industry and Pharma partnership opposing this????

Dave@Dave06031956

Hmmmmm

kaypohchee

Arch-Supremacy Member

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2005

- Messages

- 15,493

- Reaction score

- 600

https://twitter.com/DaveKeto/status/1174444986181591041

Dave Feldman@DaveKeto

Opening line: “If peer review was a drug it would never be allowed onto

market,' says Drummond Rennie, deputy editor of the Journal Of the

American Medical Association and intellectual father of the international

congresses of peer review [held every 4/yrs] since 1989.”

Quote Tweet

Nicholas Andre@nickandre

@DaveKeto when someone complains at you for not having peer

reviewed literature: “Classical peer review: an empty gun”

“we have no convincing evidence of its benefits but a lot of evidence

of its flaws.”

https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3005733/

6:07 AM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPad

Greg Domjan@GregDomjan

Peer review is like code review?

Nobody has time from their regular work, they have biases in their

preferences, limitations in current background knowledge/skills,

only looking at limited scope and not at the wider environment...

How to fix it?

Dave Feldman@DaveKeto

Of course you knew I’d immediately identify with that one.

Juan Carlos Peirano. MD@JuanPeirano

In sing song announcer voice: “Side effects of peer review may

may

include snide comments from peers whom have received unfavorable

reviews from you in the past”

paengineer@paengineer

It has been 17 years. The new generic version is PAL review.

Just as expensive and ineffective with numerous side effects.

Funny. The word comes from brother and comrade.

Not making a political statement. Mostly.

Stéphane Bernard@steph_bernard69

Many peer review studies state that peer review studies may be useful

(P< 0,00015679) ncbi.nlm.nih.go/pmc/articles/<fill in your ref...>

Travis Bost@NavyEMC

Bost@NavyEMC

“many results are made available first through conferences and the

mass media”

-I was thinking before I read this: nothing matters once the media gets it, peer reviewed or not.

-Seems review is something that may have occurred naturally 100s of

years ago, but now is a box

box

Dave Feldman@DaveKeto

Opening line: “If peer review was a drug it would never be allowed onto

market,' says Drummond Rennie, deputy editor of the Journal Of the

American Medical Association and intellectual father of the international

congresses of peer review [held every 4/yrs] since 1989.”

Quote Tweet

Nicholas Andre@nickandre

@DaveKeto when someone complains at you for not having peer

reviewed literature: “Classical peer review: an empty gun”

“we have no convincing evidence of its benefits but a lot of evidence

of its flaws.”

https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3005733/

6:07 AM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPad

Greg Domjan@GregDomjan

Peer review is like code review?

Nobody has time from their regular work, they have biases in their

preferences, limitations in current background knowledge/skills,

only looking at limited scope and not at the wider environment...

How to fix it?

Dave Feldman@DaveKeto

Of course you knew I’d immediately identify with that one.

Juan Carlos Peirano. MD@JuanPeirano

In sing song announcer voice: “Side effects of peer review

include snide comments from peers whom have received unfavorable

reviews from you in the past”

paengineer@paengineer

It has been 17 years. The new generic version is PAL review.

Just as expensive and ineffective with numerous side effects.

Funny. The word comes from brother and comrade.

Not making a political statement. Mostly.

Stéphane Bernard@steph_bernard69

Many peer review studies state that peer review studies may be useful

(P< 0,00015679) ncbi.nlm.nih.go/pmc/articles/<fill in your ref...>

Travis

“many results are made available first through conferences and the

mass media”

-I was thinking before I read this: nothing matters once the media gets it, peer reviewed or not.

-Seems review is something that may have occurred naturally 100s of

years ago, but now is a

kaypohchee

Arch-Supremacy Member

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2005

- Messages

- 15,493

- Reaction score

- 600

Anything coming from PCRM is simply not credible

https://twitter.com/DiscoStew66/status/1174601785324929024

DiscoStew@DiscoStew66

My latest clinical trial found that people on a fast food diet had more

beneficial gut bacteria, improved insulin sensitivity, and lower all-cause

mortality compared to people on a plant-based diet supplemented with

cyanide & roundup.

4:31 PM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPad

https://twitter.com/DiscoStew66/status/1174601785324929024

DiscoStew@DiscoStew66

My latest clinical trial found that people on a fast food diet had more

beneficial gut bacteria, improved insulin sensitivity, and lower all-cause

mortality compared to people on a plant-based diet supplemented with

cyanide & roundup.

4:31 PM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPad

kaypohchee

Arch-Supremacy Member

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2005

- Messages

- 15,493

- Reaction score

- 600

https://twitter.com/OZmandia/status/1174568129583648768

Shaza@OZmandia

The Problem With Sugar-Daddy Science - The Atlantic.

@usambcuba @puddleg @FructoseNo

why is science so easily corruptible?

The Problem With Sugar-Daddy Science

The pursuit of money from wealthy donors distorts the research process

—and yields flashy projects that don’t help and don’t work.

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/09/problem-sugar-daddy-science/598231/

2:17 PM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPhone

Danielle4383@Danielle43831

I would think this also applies when Merck or other drug companies fund

the safety studies of their own drugs. Conflict of interest if the ultimate goal

is to get these drugs quickly approved as “safe and effective.” #medicaltyranny

Tom@Tom49779960

Excellent article.

Shaza@OZmandia

The Problem With Sugar-Daddy Science - The Atlantic.

@usambcuba @puddleg @FructoseNo

why is science so easily corruptible?

The Problem With Sugar-Daddy Science

The pursuit of money from wealthy donors distorts the research process

—and yields flashy projects that don’t help and don’t work.

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/09/problem-sugar-daddy-science/598231/

2:17 PM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPhone

Danielle4383@Danielle43831

I would think this also applies when Merck or other drug companies fund

the safety studies of their own drugs. Conflict of interest if the ultimate goal

is to get these drugs quickly approved as “safe and effective.” #medicaltyranny

Tom@Tom49779960

Excellent article.

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/09/problem-sugar-daddy-science/598231/

The Problem With Sugar-Daddy Science

The pursuit of money from wealthy donors distorts the research process

—and yields flashy projects that don’t help and don’t work.

SEP 18, 2019

Sarah Taber

Crop scientist

The MIT Media Lab has an integrity problem. It’s not just that the lab took donations from Jeffrey Epstein and tried to conceal their source. As that news was breaking, Business Insider reported that the lab’s much-hyped “food computer” didn’t work and that staff had tried to mislead funders into thinking it did. These stories are two sides of the same problem: sugar-daddy science—the distortion of the research process by the pursuit of money from ultra-wealthy donors, no matter how shady.

Historically, research has been funded by grants. Government agencies and foundations announce that they want to fund X, and you, the scientist, write a proposal about why you’ll be awesome at X. If they agree, they give you money to do X.

That system has fallen apart. Thanks to funding cuts, getting government grants is like squeezing water from a stone. And many private foundations have, in turn, swaddled their grants in red tape. Many scientists spend more time writing grant applications than actually doing science. Private philanthropy—especially the kind that writes big, blank checks—is appealing.

The problem is, blank checks never come without strings. Something’s always exchanged: access, status, image. That’s where sugar-daddy science comes in. (Hat tip to Heidi N. Moore, who inspired the term with her Twitter critiques of what she calls sugar-daddy journalism.) Research labs cultivate plutocrats and corporate givers who want to be associated with flashy projects. Science stops being a tool to achieve things people need—clean water, shelter, food, transit, communication—and becomes a fashion accessory. If the labs are sleek, the demos look cool, and they both reflect the image the donor wants, then mission accomplished. Nothing needs to actually work.

The “food computer” was the flagship technology at the Media Lab’s Open Agriculture Initiative. The purpose of the hydroponic device was to rapidly grow plants to exact specifications. Program the right amounts of water, nutrients, and light into the plastic box, and it would automatically grow plants up to four times faster than normal. The device had all the hallmarks of sugar-daddy science: It looked amazing, and nothing added up. As a crop scientist, I’d worked in room-sized versions of this back in 2001, and the equipment was already dated by then. The speed gains its creators touted—especially when the food computer wasn’t as nearly as revolutionary or sophisticated as publicity made it out to be—just didn’t smell right.

Sure enough, the boxes did not function as promised, and news reports portray a Theranos-style deception. “Ahead of big demonstrations of the devices with MIT Media Lab funders, staff were told to place plants grown elsewhere into the devices,” Business Insider reported. “One former researcher,” declared a subsequent story in the The Chronicle of Higher Education, “described buying lavender plants from a gardening store, dusting the dirt off the roots so it looked as if they’d been grown without soil, and placing them in the food computer ahead of a photo shoot. The resulting photos were sent to news media and put on the project’s website.”

Full disclosure: When the Media Lab announced in 2017 that it was looking for innovators who didn’t have a conventional research background, I applied. I’d been working in the indoor-farm industry for years as a fixer; companies hired me for food-safety work, but then I wound up dealing with a range of brick-and-mortar problems that eluded the tech world—things like cold-chain logistics, pest control, water chemistry, security, breaking production logjams, and keeping staff from getting electrocuted. Agricultural and food-systems design is my wheelhouse. The food computer is nice, I told the Media Lab. But if you really want to knock things loose, hire me.

It didn’t. At the time, I didn’t think much of not getting the job. Agriculture is an offbeat niche for MIT, and no doubt the Media Lab had many other applicants. I already had a thriving business. No harm, no foul.

But in recent weeks—like many scientists who’ve worked real-world problems adjacent to the Media Lab—I’ve been asking why someone like me isn’t a good fit for high-profile science, but “food computer” makers and convicted pedophiles are.

The Media Lab took sugar-daddy science to a new level. Epstein’s interests in science, like a desire to “seed the human race” by impregnating dozens of women and to have his head and penis frozen after his death, were more literally sexual than most. But he didn’t invent the hustle. It’s an old philanthropy problem: Donor gratification takes precedence over results.

The MIT Media Lab already had a reputation for this before Epstein. Its One Laptop per Child project was a notorious failure. Like the food computer, it was based on a faulty premise (laptops aren’t known to actually make a difference in a child’s education), wildly oversold (the laptops were supposed to be powered by hand crank, but a working hand crank was never actually developed, and all models were powered by electrical cord), and built to fulfill donor dreams rather than a demonstrated real-world need.

A project for futuristic, bio-inspired design took $125,000 from Epstein and made him a light-up orb as a gift—over objections from students working in the project lab. This lab’s work includes, among truly visionary work like biomanufactured chitin structures, showpiece clothing demos. One set was purported to show how biodesign could help wearers survive harsh conditions on other planets. The clothes are, however, entirely nonfunctional, and were photographed on skinny, half-naked women.

How do we stop sugar-daddy science? The only long-term solution is to bring back federal funding so researchers can stop relying on donations from the beneficiaries of widening inequality. America’s competitiveness on the world stage depends on research and development. If we can’t make science that actually works, our nation is toast. Writers such as Anand Giridharadas have written relentlessly about reviving public research and other social services. This, however, has to be fixed through the democratic process, which will take time.

So what can research institutions do to ensure the integrity of their work? There are obvious solutions, such as: Don’t take money from people who are on your banned-donor list for being convicted pedophiles. Basic oversight, like financial audits, can go a long way.

Next, research and philanthropy should recognize that improving people’s lives usually involves a series of adjustments to complex systems, not a single revolutionary invention. The Boston-based nonprofit Partners in Health is a model here. It tackles problems that eluded medical charities for decades, such as drug-resistant tuberculosis, by taking on underlying issues—like the malnutrition that makes people vulnerable to TB in the first place—instead of just prescribing drugs. Instead of attempting to build a food computer, a lab could identify a more immediate need, such as cheap, easy-to-clean food-handling equipment, and invent that. No one should fear losing prestige by fixing real problems.

Finally, research needs a clear mission. The MIT Media Lab—whose mission amounted to We’re basically down for anything—was easily hijacked by social climbers and scoundrels. The pure pursuit of science, freed from worldly concerns like politics and money, is a seductive illusion. In reality, it ends up attracting the very worst people.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

SARAH TABER, a crop scientist and industry consultant, holds a doctorate in crop health. She is the host of the podcast Farm to Taber and is working on a book about the effect of human systems on American agriculture.

kaypohchee

Arch-Supremacy Member

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2005

- Messages

- 15,493

- Reaction score

- 600

https://twitter.com/DiscoStew66/status/1174543055052951552

DiscoStew@DiscoStew66

Humans, the only creature smart enough to invent fake meat and dumb enough to eat it...

Critics Challenge the Health Benefits of Alternative Meats

First, there were plants. Then came plant-based products, like tempeh,

made from fermented soybeans, and veggie burgers, mash-ups of

vegetables and legumes.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/arti...l-threat-with-opponents-attacking-healthiness

12:37 PM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter Web Client

Keto cyclist Ⓚ@KetoCyclist

I don't quite believe the 'craze' that is these fake meats.

I think the social media people are being paid to promote them.

Every time i see this shi* on the menu, I ask the waiter/waitress/cashier

how many they sell. Each response is "hardly any".

©arniWay.nyc - Travis Statham@Travis_Statham

Barry Groves just clapped from the grave.

Dr Mat Hunt@Mat_Hunt

Mostly vegans though...

jackbennett.co, PhD@jackbennett_co

"But while there’s scientific consensus that human health and the

planet’s would benefit from a shift to more plant-based foods" [CITATION NEEDED]

janiceingramsa@janiceingramsa1

Puzzling why they hate it so much but want to be reminded of

what it “looks” like. Humph...

CFC@CoucouCfc

Here comes the troll and hater of all thing related to veganism.

DiscoStew@DiscoStew66

I’m actually a vegan thou I do take supplements (eg red meat, fish, chicken, eggs, bacon, dairy)...

CFC@CoucouCfc

It really doesn't bother me what you eat.

I'm vegan but rarely annoy meat eater by tweeting studies about

meat consumption. Been there done that.

DiscoStew@DiscoStew66

Humans, the only creature smart enough to invent fake meat and dumb enough to eat it...

Critics Challenge the Health Benefits of Alternative Meats

First, there were plants. Then came plant-based products, like tempeh,

made from fermented soybeans, and veggie burgers, mash-ups of

vegetables and legumes.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/arti...l-threat-with-opponents-attacking-healthiness

12:37 PM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter Web Client

Keto cyclist Ⓚ@KetoCyclist

I don't quite believe the 'craze' that is these fake meats.

I think the social media people are being paid to promote them.

Every time i see this shi* on the menu, I ask the waiter/waitress/cashier

how many they sell. Each response is "hardly any".

©arniWay.nyc - Travis Statham@Travis_Statham

Barry Groves just clapped from the grave.

Dr Mat Hunt@Mat_Hunt

Mostly vegans though...

jackbennett.co, PhD@jackbennett_co

"But while there’s scientific consensus that human health and the

planet’s would benefit from a shift to more plant-based foods" [CITATION NEEDED]

janiceingramsa@janiceingramsa1

Puzzling why they hate it so much but want to be reminded of

what it “looks” like. Humph...

CFC@CoucouCfc

Here comes the troll and hater of all thing related to veganism.

DiscoStew@DiscoStew66

I’m actually a vegan thou I do take supplements (eg red meat, fish, chicken, eggs, bacon, dairy)...

CFC@CoucouCfc

It really doesn't bother me what you eat.

I'm vegan but rarely annoy meat eater by tweeting studies about

meat consumption. Been there done that.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/arti...l-threat-with-opponents-attacking-healthiness

Critics Challenge the Health Benefits of Alternative Meats

By Leslie Patton and Lydia Mulvany

18 September 2019, 22:28 GMT+8

-Competing PR blitzes over nutrition and processing claims

-Some shun meat mimickers because they’re not ‘whole’ foods

First, there were plants. Then came plant-based products, like tempeh, made from fermented soybeans, and veggie burgers, mash-ups of vegetables and legumes.

Those days seem so innocent and uncomplicated. Now the world is grappling with the Beyond Meat and Impossible Burger craze, which has made investors giddy and spurred the health police to ask uncomfortable questions. Aren’t the products that look and taste like actual meat just the latest suspect offerings from the processed-food complex?

The answer is, basically, it depends. The debate rages, as do the competing public relations blitzes. Consumers have to figure it out. The companies making the alternatives should take note.

Read More: Protein ‘Shake-Up’ Seen Pushing Faux Meat Market to $240 Billion

The stakes are high for Beyond Meat Inc., a Wall Street darling whose stock trades more than six times its early May debut price. The company’s main product, like the one from Impossible Foods Inc., is a burger that is remarkably similar to the kind made from ground beef and even turns brown as it cooks.

Impossible patties stacked at the Impossible Foods manufacturing facility in Oakland, California.Source: Anthony Lindsey Photography/Impossible Foods

Some fans see the patties as ethical choices; cows produce methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, and grass-fed cattle ranching is cited as a main cause for increasing destruction of the Amazon in Brazil.

But while there’s scientific consensus that human health and the planet’s would benefit from a shift to more plant-based foods, there’s no agreement about how the newest generation of plant-based meat mimickers fit in.

Beef Versus Veggie Burger Nutrition

[Diagrams & Info not reproducible ...]

Source: Product nutrition labels

Note: Serving size of the veggie burgers ranges from 2.3 to 4 ounces.

A study in the Journal of the American Medical Association, while noting the risks of diets high in red meat, said people should be “cautious” about the health effects of plant-based alternatives that use purified plant proteins rather than whole foods.

Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc., for one, has said it won’t serve these sorts of meat alternatives because they aren’t pure enough for the chain’s “food with integrity” policy. (The chain’s vegetarian option is a mix of spices and shredded tofu, a soy product that, because it has been altered from its original form, is technically processed, though, the argument goes, not as processed as some alternatives.)

Meanwhile, a group called the Center for Consumer Freedom bought full-page advertisements last month in the Wall Street Journal and New York Post that trashed plant-based meat alternatives as chemical-laden fakes.

“The public is being misled,” said Niko Davis, a spokesman for the nonprofit, which declined to disclose the companies or individuals providing funding. Its website describes its mission as opposing a “cabal of activists” that is against personal choice, such as “health campaigners, trial lawyers, personal-finance do-gooders, animal-rights misanthropes and meddling bureaucrats.”

Davis said the group isn’t working with the real-meat industry, though the message is similar. Beef is an “overall better nutritional package without a lot of added sodium” or other additives, said Shalene McNeill, a nutritionist for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association.

One target for the critics has been the ingredient heme in the Impossible Burger, which is on menus at the Burger King, White Castle, Red Robin and Qdoba chains and thousands of other restaurants. Heme is mass-produced by fermenting a genetically modified yeast. Some of the hubbub died down after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration said it doesn’t have a problem with it, announcing plans to amend rules to call the use of heme safe as a color additive in imitation beef.

According to Impossible, the attacks are all part of a “smear campaign to sow fear and doubt about plant-based meat.” The company said its burgers and other offerings are better for people than animal products, delivering as much protein and bioavailable iron as beef without the associated downsides. And “processed” criticism doesn’t fly, it said in a statement, given that all food involves some kind of processing.

Beyond makes similar claims about its foods. “We know that consumers are increasingly pulling away from red and processed meat because of the levels of cholesterol and associated health baggage,” said Will Schafer, vice president of marketing. The company also touts what it calls a simple production process that’s more humane and sustainable than livestock production.

There’s a lot of competition out there and on its way for Beyond and Impossible, including from Kellogg Co. and Tyson Foods Inc., which sold its stake in Beyond before that company went public. The Native Foods vegan chain and Ted’s Montana Grill, co-founded by Ted Turner, are making their own veggie burgers, emphasizing what they call “whole” ingredients.

“It just seems to go against the grain to me if you want to eat healthier that you would choose manufactured, chemically-produced products,” said George McKerrow, Ted’s chief executive officer and co-founder.

As to the question about nutrition, Impossible and Beyond burgers aren’t necessarily a healthier choice, said Bonnie Liebman, director of nutrition at Center for Science in the Public Interest. Especially if you’re eating out, it’s a tie. “The bottom line is that all burgers at restaurants are too high in calories, saturated fat, and sodium, whether beef or plant-based.”

And not all veggie burgers are created equal. Four dozen vegetarian patties by the leading brands range from 4 to 18 grams of fat, and between 2 and 28 grams of protein. A single four ounce 80/20 beef patty contains 19.4 grams of protein and 22.6 grams of fat. The veggie burgers’ sodium counts goes from 200 to 630 milligrams, 27% of the recommended daily value.

Gene Grabowski, a partner at the communications firm kglobal, predicted a long fight between the real-meat and fake-meat forces. Much is at stake. A Barclays reports estimates the plant-based sector could reach $140 billion in sales globally in the next decade.

“What’s playing out now are a lot of claims. There’s a lot of confusion,” he said. Consumers will decide who wins. “Ultimately, it’s up to them.”

— With assistance by Hannah Recht

kaypohchee

Arch-Supremacy Member

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2005

- Messages

- 15,493

- Reaction score

- 600

https://twitter.com/LouiseStephen9/status/1174524794613592066

Louise Stephen@LouiseStephen9

Anyway, let’s turn the world vegan by 2050 *

*

Pregnant women with anaemia before 30 weeks 'more likely to have

children with autism and ADHD'

Children born to anaemic mothers 'more likely to have autism and ADHD'

Half a million Swedish children and their mothers were studied

Anaemia was also linked to higher rates of intellectual disability.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/...mia-30-weeks-likely-children-autism-ADHD.html

11:25 AM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPhone

superbirdman©@superbirdman1

what's good for healthcare companies, isn't good for our health

Dave@Dave06031956

More Medications snd money for the big Pharma...

Margaret Gibson@migib20

What a brave new world that has such people in it.

Extracts :

Women who get anaemia early in pregnancy are more likely to have children with autism, a study suggests.

The condition – common in mothers-to-be – is also linked to higher rates of ADHD and intellectual disabilities in children.

Researchers looked at nearly 300,000 mothers of more than 500,000 children born in Sweden between 1987 and 2010.

But the scientists found the chances were no greater in mothers who received an anaemia diagnosis later on in their pregnancy - after 30 weeks.

Up to 20 per cent of pregnant women worldwide suffer from anaemia, according to estimates.

Lead researcher Dr Renee Gardner said: ‘A diagnosis of anaemia earlier in pregnancy might represent a more severe and long-lasting nutrition deficiency for the foetus.

‘Different parts of the brain and nervous system develop at different times during pregnancy.

'So an earlier exposure to anemia might affect the brain differently compared to a later exposure.’

Dr James Findon, a lecturer in psychology at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, said: 'This study supports previous work suggesting a link between maternal iron deficiency and autism.

'That said, this study does not provide evidence of "cause and effect".

'We know that iron is very important in brain development and that iron deficiency during pregnancy is associated with poorer developmental outcomes.'

Previous studies have discovered an iron deficiency early in life can impair a child’s motor, language and behavioural development.

Iron is necessary for the development for some neurotransmitters, which may be impaired in the brains of those with autism and ADHD.

Louise Stephen@LouiseStephen9

Anyway, let’s turn the world vegan by 2050

Pregnant women with anaemia before 30 weeks 'more likely to have

children with autism and ADHD'

Children born to anaemic mothers 'more likely to have autism and ADHD'

Half a million Swedish children and their mothers were studied

Anaemia was also linked to higher rates of intellectual disability.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/...mia-30-weeks-likely-children-autism-ADHD.html

11:25 AM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPhone

superbirdman©@superbirdman1

what's good for healthcare companies, isn't good for our health

Dave@Dave06031956

More Medications snd money for the big Pharma...

Margaret Gibson@migib20

What a brave new world that has such people in it.

Extracts :

Women who get anaemia early in pregnancy are more likely to have children with autism, a study suggests.

The condition – common in mothers-to-be – is also linked to higher rates of ADHD and intellectual disabilities in children.

Researchers looked at nearly 300,000 mothers of more than 500,000 children born in Sweden between 1987 and 2010.

But the scientists found the chances were no greater in mothers who received an anaemia diagnosis later on in their pregnancy - after 30 weeks.

Up to 20 per cent of pregnant women worldwide suffer from anaemia, according to estimates.

Lead researcher Dr Renee Gardner said: ‘A diagnosis of anaemia earlier in pregnancy might represent a more severe and long-lasting nutrition deficiency for the foetus.

‘Different parts of the brain and nervous system develop at different times during pregnancy.

'So an earlier exposure to anemia might affect the brain differently compared to a later exposure.’

Dr James Findon, a lecturer in psychology at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, said: 'This study supports previous work suggesting a link between maternal iron deficiency and autism.

'That said, this study does not provide evidence of "cause and effect".

'We know that iron is very important in brain development and that iron deficiency during pregnancy is associated with poorer developmental outcomes.'

Previous studies have discovered an iron deficiency early in life can impair a child’s motor, language and behavioural development.

Iron is necessary for the development for some neurotransmitters, which may be impaired in the brains of those with autism and ADHD.

kaypohchee

Arch-Supremacy Member

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2005

- Messages

- 15,493

- Reaction score

- 600

https://twitter.com/FatEmperor/status/1173680148119506944

Ivor Cummins@FatEmperor

Jaysus here we go - misinformation never felt so bad:

https://plantbasednews.org/film/the-game-changers-out-today

#Yes2Meat #meatheals

Vegan Documentary The Game Changers Out Today

Tickets for the world premiere are beginning to sell out

plantbasednews.org

https://youtu.be/iSpglxHTJVM

'Best athletes on the planet'

3:28 AM · Sep 17, 2019·Twitter Web App

https://twitter.com/janvyjidak/status/1174579712305303552

Jan Vyjidak@JAnvyjidak

Novak had to reintroduce meat back into diet as a condition for Marian

Vajda to resume collaboration before Wimbledon 2018.

I find Novak’s support for this “documentary” a big disappointment.

3:03 PM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPhone

David Wyant@wyadvd

And a little bit fraudulent .

At least @HumanTimothy was honest .He withdrew.

Jan Vyjidak@janvyjidak

Why did he withdraw?

David Wyant@wyadvd

He became an omnivore , then phoned the producer of the film to say he couldn’t do the film in good conscience .

Human Performance Outliers Podcast: Episode 148: Tim Shieff on Apple Podcasts

Show Human Performance Outliers Podcast, Ep Episode 148: Tim Shieff

- 16 Aug 2019

podcasts.apple.com

Mark Gossage@bulkbiker

I'm guessing that whenever one of them gets in their multiple cars their bum rests on nice leather.

I doubt a single one of them is "vegan" in its truest sense.

"Look at me... my personal chef can cook some veggies" ...

... etc ...

Brad Lemley@BradCLemley

Ivor, a question. The U.S. has decided that trans fats are unhealthy, and

they are essentially banned here.

But now, pure soybean oil boils away in a million deep-fry vats.

Is it any better for health?

I suspect due to its ability to oxidize it's actually worse.

Ivor Cummins@FatEmperor

Scary filth I would say

Christian Assad, MD@ChristianAssad

If it wasn't for meat it is unlikely that Arnie would have been Conan

or the Terminator.

- I'll continue enjoying my Steak and Salmon.

Brian FitzGerald@BrianGFitz

The steroids helped though

Christian Assad, MD@ChristianAssad

LOL steroids and steak work synergistically. Doubt he would have

gotten there with roids and Lupini beans

Brian FitzGerald@BrianGFitz

He did love a steak

Al Hunt@mister_hunt

I suspect he still may....

Leo@LittleOlMe97

I suppose Cam Newton will not be mentioned? Two games into his

vegan diet and his performance has slipped appreciably.

....

Last edited:

kaypohchee

Arch-Supremacy Member

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2005

- Messages

- 15,493

- Reaction score

- 600

https://twitter.com/LouiseStephen9/status/1174534721449033728

Louise Stephen@LouiseStephen9

Hope those pushing veganism and meat fear in the name of climate change take the time to watch this testimony. Take time to consider the harm you

are inflicting on innocent young people.

Quote Tweet

MS @michael54652438

@michael54652438

Awesome ex vegan tells the truth about the lies and dangers of veganism

in emotional recount of her own experience in this “eating disorder” beautifully put.

More young people need to see this.

#vegan #exvegan #meatheals

@SBakerMD #veganlies #veganism

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=Waf-lOy3700

12:04 PM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPhone

heather

@feather1952

@feather1952

We are human animals that are meant to eat meat. The natural law of

things is eat or be eaten but that doesn’t mean we can’t eat ethically.

Factory farming, big business is where I have my issues. I try to always

buy my meat organic & local.

Al Hunt@mister_hunt

I agree. Buy the best you can afford; top of the list would be ethically farmed and organic.

Louise Stephen@LouiseStephen9

Hope those pushing veganism and meat fear in the name of climate change take the time to watch this testimony. Take time to consider the harm you

are inflicting on innocent young people.

Quote Tweet

MS

Awesome ex vegan tells the truth about the lies and dangers of veganism

in emotional recount of her own experience in this “eating disorder” beautifully put.

More young people need to see this.

#vegan #exvegan #meatheals

@SBakerMD #veganlies #veganism

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=Waf-lOy3700

12:04 PM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPhone

heather

We are human animals that are meant to eat meat. The natural law of

things is eat or be eaten but that doesn’t mean we can’t eat ethically.

Factory farming, big business is where I have my issues. I try to always

buy my meat organic & local.

Al Hunt@mister_hunt

I agree. Buy the best you can afford; top of the list would be ethically farmed and organic.

Yui Nagase

Senior Member

- Joined

- Sep 19, 2019

- Messages

- 1,500

- Reaction score

- 0

you have aspergers right?

kaypohchee

Arch-Supremacy Member

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2005

- Messages

- 15,493

- Reaction score

- 600

[*NOT for KPC-HATERS*]Why the War on Meat & Related Topics ....

https://twitter.com/itsjillgardner/status/1174795428606484480

The Fat Controller @itsjillgardner

@itsjillgardner

Eat Meat: Beat Depression

https://sustainabledish.com/eat-meat-beat-depression/

@SustainableDish

Eat Meat: Beat Depression

Anxiety and depression are debilitating, but surmounting research is

finding that people who eat meat are less depressed.

sustainabledish.com

5:20 AM · Sep 20, 2019 from Milton Keynes, England·Twitter for iPhone

..............................................

https://twitter.com/DefendingBeef/status/1174736240379191297

Defending Beef@DefendingBeef

Food For Thought: Meat-Based Diet Made Us Smarter-

Food For Thought: Meat-Based Diet Made Us Smarter

Our earliest ancestors ate a diet of raw food that required immense energy

to digest. But once we started eating nutrient-rich meat, our

energy-hungry brains began growing and our guts began to...

https://www.npr.org/2010/08/02/128849908/food-for-thought-meat-based-diet-made-us-smarter?sc=tw

1:25 AM · Sep 20, 2019·Twitter Web Client

.........................................

https://twitter.com/drsplace/status/1174671560558481408

Sara Place@drsplace

What if we could put all the VC $$ invested in new food products in

wealthy nations meant to “disrupt the food system” into improving

livelihoods of livestock producers around the &

&  access to safe, nutritious animal source food?

access to safe, nutritious animal source food?

What’s the ROI to humanity difference?

Quote Tweet

Marchmont Comms@MarchmontComms

Alt-meat is not the answer for poorer countries, writes

@isabaltenweck @ILRI, for @ftopinion.

"It is time we recognised the vital role livestock plays across the

world’s developing economies."

#LivestockAgenda

https://ft.com/content/cca976ec-d623-11e9-8d46-8def889b4137

9:08 PM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPhone

Nutrional sceptic.@fuelled_by_keto

Not to mention the vital role of organic fertiliser.

Sara Place@drsplace

Yes, livestock are more than a source of food, which is true in the USA

and around the world

CR Chandrasekar@crc8

do animals make new fertiliser?

Southern Plains Perspective@PlainsSouthern

And what if we looked at our current farm programs with an eye toward pushing incentives to folks who incorporated livestock w/other soil

health practices to both feed the world & protect the environment?

Maybe a per acre sustainability direct payment?

That’s a green new deal

Southern Plains Perspective@PlainsSouthern

In my opinion we need more animals and better grazing practices, not less

CR Chandrasekar@crc8

let VC money help scalability and sustainabilty

Southern Plains Perspective@PlainsSouthern

I like the idea but what’s the hook for them to invest?

Also, how many producers would they be able to work with and

conversely l how many would be willing to work with them?

CR Chandrasekar@crc8

@isabaltenweck

1. there will always be a place for animals in global food

- and eco-systems, but

2. industrial animal killing for food will neither scale in time,

nor sustainably, to feed the over 5 billion people who have no meat as

known in the west today

Jesse Hoff@hoffsbeefs

Billion dollar question

Wynn Lare@RippleCreekNW

VC wants eady & quick exits.

They aren't investing for long term.

Angel funding on-up through series rounds is tightly controlled & scheduled.

Why ?

VCs are OCD-lite-or-better-nerds.

We posess this awareness (or not).

VC now involved with food; it's worth learning their world

Sir Joel@BlazekJoel

Yes! And how about a delivery method for locally raised, sustainable food sources? Eat what doesn't have to travel more than 100 miles. Farms to households.

.....................................

https://twitter.com/anahadoconnor/status/1174932991753109506

anahad oconnor@anahadoconnor

Jeff Bezos unveils sweeping plan to tackle climate change

Jeff Bezos unveils sweeping new plan to tackle climate change

The Amazon CEO spoke in Washington D.C. about the company's

sustainability efforts.

https://www.cnbc.com/2019/09/19/jef...c.html?__source=sharebar|twitter&par=sharebar

2:27 PM · Sep 20, 2019·Twitter Web Client

Jeff Bezos unveils sweeping plan to tackle climate change

PUBLISHED THU, SEP 19 2019 10:08 AM EDTUPDATED THU, SEP 19 2019 12:35 PM EDT

Annie Palmer@ANNIERPALMER

KEY POINTS

- Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos unveils a sweeping new plan to tackle climate change.

- Bezos says Amazon is committed to meet the goals of the Paris climate agreement 10 years early.

- As part of the plan, Amazon has agreed to purchase 100,000 electric delivery vans from vehicle manufacturer Rivian.

- Bezos expects 80% of Amazon’s energy use to come from renewable sources by 2024, before transitioning to zero emissions by 2030.

WATCH NOW

VIDEO 02:46

Amazon to meet Paris climate goals 10 years ahead of schedule

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos unveiled a sweeping new plan on Thursday to tackle climate change, committing the retail giant to meet the goals of the Paris climate agreement 10 years ahead of schedule.

In what he is calling the “Climate Pledge,” Bezos also promised to measure and report the company’s emissions on a regular basis, implement decarbonization strategies and alter its business strategies to offset remaining emissions.

Bezos expects 80% of Amazon’s energy use to come from renewable sources by 2024, up from a current rate of 40%, before transitioning to zero emissions by 2030.

“We want to use our scale and our scope to lead the way,” Bezos said at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. “One of the things we know about Amazon as a role model for this is that it’s a difficult challenge for us because we have deep, large physical infrastructure. So, if we can do this, anyone can do this.”

The plan calls for other companies to join Amazon in pledging to have net zero carbon emissions by 2040 — a decade ahead of the Paris accord’s goal.

As part of the announcement, Amazon has agreed to purchase 100,000 electric delivery vans from vehicle manufacturer Rivian.

Bezos said the first electric delivery vans will be on the road by 2021, and he estimates 100,000 vehicles will be deployed by 2024. The move builds on Rivian’s $700 million investment round in February, which was led by Amazon. Amazon has invested $440 million in Rivian, the announcement said.

Dave Clark@davehclark

Our fleet is Electrifying! Thrilled to announce the order of 100,000 electric delivery vehicles – the largest order of electric delivery vehicles ever.

Look out for the new vans starting in 2021.

Amazon will work with companies in its supply chain to help them decarbonize and reach the same goals outlined in the plan. It also plans to meet with other large corporations to get them to sign onto the agreement.

The company also announced a $100 million donation to The Nature Conservancy to form the Right Now Climate Fund, which will work to restore and protect forests, wetlands and peatlands around the world, with the goal of removing carbon from the atmosphere.

Dara O’Rourke, a senior principal scientist on Amazon’s sustainability team, said the company built a “comprehensive” carbon accounting system that helps it pull data from its various businesses.

“Amazon is as complex as many companies combined,” O’Rourke said. “That forced us to build one of the most sophisticated carbon accounting systems in the world. We had to build a system that had the granular data, but at an Amazon scale.”

The Paris climate agreement of 2015 seeks to limit global warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius and meaningfully reduce man-made emissions by 2050. In 2017, President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the landmark accord — a decision that has since attracted widespread scrutiny. Additionally, Trump and Bezos have sparred on several occasions, with Trump focusing his ire on the newspaper Bezos owns, The Washington Post.

Bezos’ plan comes as Amazon faces mounting pressure from employees to address its environmental impact.

At Amazon’s annual shareholder meeting in May, thousands of employees submitted a proposal asking Bezos to develop a comprehensive climate-change plan and reduce its carbon footprint, though it was ultimately rejected. The proposal was built on an employee letter published in April that accused Amazon of donating to climate-delaying legislators and urged the company to transition away from fossil fuels.

Additionally, over 1,000 Amazon employees have said they plan to walk out on Friday as part of the Global Climate Strike, of which Google and Microsoft employees also plan to participate. The employee walkout represents the first strike at Amazon’s Seattle headquarters in the company’s 25-year history, according to Wired.

When asked about the employee walkouts, Bezos said that while he doesn’t support all of Amazon employees’ demands, he understands why people are passionate about climate change. Among the specific demands Bezos said he doesn’t support is ending AWS’ cloud contracts with fossil fuel companies.

“The global strike tomorrow, I think it’s totally understandable,” he said. “We don’t want this to be the tragedy of the commons. We all have to work together on this.”

He added that Amazon is committed to looking at its campaign contributions to determine whether they include “active climate deniers.” The company also intends to focus more lobbying efforts in Washington around political solutions to climate change, Bezos said.

The company has taken previous steps to address climate change. In February, Amazon announced it would make half of all its shipments carbon neutral by 2030 by using more eco-friendly packaging, using more renewable energy like wind power, as well as using electric vans for package deliveries. As part of that effort, which it calls “Shipment Zero,” Amazon said it would share its company-wide carbon footprint for the first time later this year.

VIDEO 19:16

How Amazon fends off unions as labor rights groups rally workers to protest

..............................................

https://twitter.com/drjoesDIYhealth/status/1174887823217844225

Dr Joe@drjoesDIYhealth

The tolerance and inclusivity is just awesome.

Quote Tweet

Charlotte Mortlock@CMMortlock

Just out here doing my job, covering the climate strike rally in Sydney.

A demonstrator comes up to me and asks who I work for so I told her.

She replied “I hope you can never have children.”

Very inclusive. Very woke. Very kind.

11:27 AM · Sep 20, 2019·Twitter for iPhone

https://twitter.com/itsjillgardner/status/1174795428606484480

The Fat Controller

Eat Meat: Beat Depression

https://sustainabledish.com/eat-meat-beat-depression/

@SustainableDish

Eat Meat: Beat Depression

Anxiety and depression are debilitating, but surmounting research is

finding that people who eat meat are less depressed.

sustainabledish.com

5:20 AM · Sep 20, 2019 from Milton Keynes, England·Twitter for iPhone

..............................................

https://twitter.com/DefendingBeef/status/1174736240379191297

Defending Beef@DefendingBeef

Food For Thought: Meat-Based Diet Made Us Smarter-

Food For Thought: Meat-Based Diet Made Us Smarter

Our earliest ancestors ate a diet of raw food that required immense energy

to digest. But once we started eating nutrient-rich meat, our

energy-hungry brains began growing and our guts began to...

https://www.npr.org/2010/08/02/128849908/food-for-thought-meat-based-diet-made-us-smarter?sc=tw

1:25 AM · Sep 20, 2019·Twitter Web Client

.........................................

https://twitter.com/drsplace/status/1174671560558481408

Sara Place@drsplace

What if we could put all the VC $$ invested in new food products in

wealthy nations meant to “disrupt the food system” into improving

livelihoods of livestock producers around the

What’s the ROI to humanity difference?

Quote Tweet

Marchmont Comms@MarchmontComms

Alt-meat is not the answer for poorer countries, writes

@isabaltenweck @ILRI, for @ftopinion.

"It is time we recognised the vital role livestock plays across the

world’s developing economies."

#LivestockAgenda

https://ft.com/content/cca976ec-d623-11e9-8d46-8def889b4137

9:08 PM · Sep 19, 2019·Twitter for iPhone

Nutrional sceptic.@fuelled_by_keto

Not to mention the vital role of organic fertiliser.

Sara Place@drsplace

Yes, livestock are more than a source of food, which is true in the USA

and around the world

CR Chandrasekar@crc8

do animals make new fertiliser?

Southern Plains Perspective@PlainsSouthern